While numerous political commentators have offered up their opinion about who won or lost last week’s GOP debate, we here at the Lazer Lab at Northeastern University spent the last week looking at the numbers. Actually, we looked at the words: What did candidates actually talk about? How much did they talk, and for how long? The answers gave us three new ways to think about what mattered in the debate, and who won.

- Home

- 21st Century Democracy

21st Century Democracy

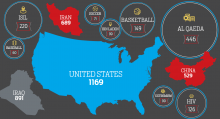

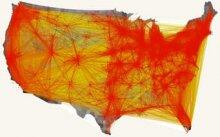

Democrats talk about Iraq; Republicans talk about.........Panama? This week is a big one for America’s global relations. While Congress started hashing out whether to hand the president authority to finish the largest trade deal in history, Obama was wrapping up the G-7 economic summit in Germany. Beneath the talking points, what are America’s real priorities when it comes to the rest of the world? We decided to analyze what Congress actually talks about with it discusses foreign affairs - essentially, to draw a map of the world as seen from Capitol Hill. We took all the public statements of members of Congess from 2009 to 2014 (thanks go to VoteSmart for compiling them) and crunched them to see what countries Democrats and Republicans talk about, how their lists differ, and they view those countries as connected.

It’s too easy to be led astray by the lure of big data. Google Flu Trends has long been the go-to example for anyone asserting the revolutionary potential of big data. Since 2008 the company has claimed it could use counts of flu-related Web searches to forecast flu outbreaks weeks ahead of data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Unfortunately, this turned out to be what i call big-data hubris. Colleagues and I recently showed that Google’s tool had drifted further and further from accurately predicting CDC data over time. Among the underlying problems was that Google assumed a constant relationship between flu-related searches and flu prevalence, even as the search technology changed and people began usingit in different ways.

In politics, it’s become conventional wisdom that talking seriously to regular Americans doesn’t really pay off. Numerous studies have found that citizens appear to dig in their heels, resisting information that contradicts their beliefs - if they’re informed enough to have meaningful beliefs in the first place. When politicians talk to voters, the goal is usually to rev up their base, or shift a tiny wedge of the "undecided," rather to genuinely persuade a broad swath of the public. This might be a discouraging view of how politics works, but it’s also seen as realistic. If Americans aren’t persuadable, there’s little sense in members of Congress wasting their time trying to have meaningful conversations about the future of the country. This view is also mostly wrong.

Barack Obama can spin a good phrase, and while his political opponents like to say his actions don’t always match his soaring rhetoric, there’s no denying the man has said a lot: So far in his presidency, he’s given more than 2,000 official speeches, uttering about 3.5 million different words. So what has he actually been telling us? To answer this question in a whole new way, we analysed all of Obama’s speeches through the end of September and looked at how frequently different terms came up. Surprises abound: Afghanistan was the most-mentioned country after the United States. He talks football more than basketball, Pelosi more than Reid and "change" more than "hope" - except in 2012. Here’s a unique look at what’s really on Obama’s mind.

Every day, millions of people use Google to dig up information that drives their daily lives, from how long their commute will be to how to treat their child’s illness. This search data reveals a kit about the searchers: their wants, their needs, their concerns - extraordinarily valuable information. If these searches accurately reflect what is happening in people’s lives, analysts could use this information to track diseases, predict sales of new products, or even anticipate the results of elections.

Crunching the words, experts find Trump got the attention, Rubio made the most of his chances and Jeb squandered them. A lot of ink has been spilled over last Wednesday’s debate, but here’s another way to talk about it. Judging purely by the data, Trump still dominated - but Fiorina and Christie really stepped forward, and Rubio made the most of the openings he had. Jeb Bush, meanwhile, had plenty of chances but largely let them slip by.

The use of socio-technical data to predict elections is a growing research area. We argue that election prediction research suffers from under-specified theoretical models that do not properly distinguish between ’poll-like’ and ’prediction market-like’ mechanisms understand findings. More specifically, we argue that, in systems with strong norms and reputational feedback mechanisms, individuals have market-like incentives to bias content creation toward candidates they expect will win. We provide evidence for the merits of this approach using the creation of Wikipedia pages for candidates in the 2010 US and UK national legislative elections. We find that Wikipedia editors are more likely to create Wikipedia pages for challengers who have a better chance of defeating their incumbent opponent and that the timing of these page creations coincides with periods when collective expectations for the candidate’s success are relatively high.

Do formal deliberative events influence larger patterns of political discussion and public opinion? Critics argue that only a tiny number of people can participate in any given gathering and that deliberation may not remedy - and may in fact exacerbate - inequalities. We assess these criticisms with an experimental design merging a formal deliberative session with data on participants’ social networks. We conducted a field experiment in which randomly selected constituents attended an online deliberative session with their U.S. Senator. We find that attending the deliberative session dramatically incresed interpersonal political discussion on topics relating to the event. Importantly, after an extensive series of moderation checks, we find that no participant/nodal charactersitics or dyadic/network characteristics, conditioned these effects; this provides reassurance that observed, positive spillovers are not limited to certain portions of the citizenry. The results of our study suggest that even relatively small-scale deliberative encounters can have a broader effect in the mass public, and that these events are equal-opportunity multipliers.

We examine the social antecedents of contributing to campaigns, with a particular focus on the role of population density and social networking opportunities. Using 10 years of US campaign contribution data from the Federal Election Commission and a national survey of party leaders, we find that recruiting contributors is easier in a densely populated region, where the daily opportunity of individuals being exposed to the same information via their social networks is high. Furthermore, the effect of population density is heterogeneous with respect to mobility: if a region has substantial commuting outflow, the chance of being mobilized from the place of residence decreases, but the chance of mobilization in their place of work increases. This analysis also reveals differences between political parties. Democrats are more dependent on social netowrking in population dense areas. This difference in the importance of social networking opportunities present in geographical space helps explain macro-level patterns in party fundraising.

"Man is by nature a political animal," as asserted by Aristotle. This political nature manifests itself in the data we produce and the traces we leave online. In this tutorial, we address a number of fundamental issues regarding mining of political data: What types of data would be considered political? What can we learn from such data? Can we use the data for prediction of political changes, etc? How can these prediction tasks be done efficiently? Can we use online socio-political data in order to get a better understanding of our political systems and of recent political changes? What are the pitfalls and inherent shortcomings of using online data for political analysis? In recent years, with the abundance of data, these questions, among others, have gained importance, especially in light of the global political turmoil and the upcoming 2016 US presidential election. We introduce relevant political science theory, describe the challenges within the framework of computational social science and present state of the art approaches bridging social network analysis, graph mining, and natural language processing.