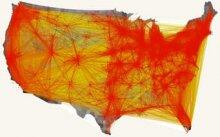

Political Networks

Politics is necessarily a relational construct

There are a variety of canonical definitions of politics—the study of power; the study of the authoritative distribution of resources, and so on—but they all have embedded in them a relational notion. Consider that core construct of political science: power. One should not ask "who is powerful"-- rather, one should ask who has power over whom. Power is not an attribute of (say) an individual, but is a statement of a particular structure of interdependence. The President of my university may have some power over me—but the President of another university would not; and surely that power vis a vis particular individuals is finely differentiated.

Political science largely drifted away from this construction of politics, in part because of powerful statistical methods that assume independence among units (often a reasonable assumption for statistical models, but a problematic axiom for the study of social systems). My research has tried to bring this network dimension into the study of politics, with studies ranging from the spread of trade agreements in the 19th century (I argue that the spread was emergent rather than a reflection of hegemonic preferences), to interest groups, to social influence on political opinions.

I have also served as a founder and host (in 2008 and 2009) of the annual Political Networks conference.

2008: http://www.hks.harvard.edu/netgov/html/colloquia_NIPS_conference_schedule.html

2009: http://www.hks.harvard.edu/netgov/html/colloquia_HPNC2009.htm