This study reports the results of a multiyear program to predict direct executive elections in a variety of countries from globally pooled data. We developed prediction models by means of an election data set covering 86 countries and more than 500 elections, and a separate data set with extensive polling data from 146 election rounds. We also participated in two live forecasting eperiments. Our models correctly predicted 80 to 90% of elections in out-of-sample tests. The results suggest that global elections can be successfully modeled and that they are likely to become more predictable as more information becomes available in future elections. The results provide strong evidence for the impact of political institutions and incumbent advantage. They also provide evidence to support contentions about the importance of international linkage and aid. Direct evidence for economic indicators as predictors of election outcomes is relatively weak. The results suggest that with some adjustments, global polling is a robust predictor of election outcomes, even in developing states. Implications of these findings after the latest U.S. presidential election are discussed.

2017

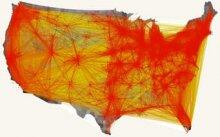

We examine the social antecedents of contributing to campaigns, with a particular focus on the role of population density and social networking opportunities. Using 10 years of US campaign contribution data from the Federal Election Commission and a national survey of party leaders, we find that recruiting contributors is easier in a densely populated region, where the daily opportunity of individuals being exposed to the same information via their social networks is high. Furthermore, the effect of population density is heterogeneous with respect to mobility: if a region has substantial commuting outflow, the chance of being mobilized from the place of residence decreases, but the chance of mobilization in their place of work increases. This analysis also reveals differences between political parties. Democrats are more dependent on social netowrking in population dense areas. This difference in the importance of social networking opportunities present in geographical space helps explain macro-level patterns in party fundraising.

2016

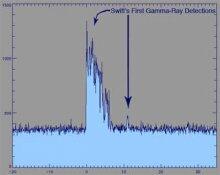

There have been serious efforts over the past 40 years to use newspaper articles to create global-scale databases of events occurring in every corner of the world, to help understand and shape responses to global problems. Although most have been limited by the technology of the time (1) [see supplementary materials (SM)], two recent groundbreaking projects to provide global, real-time "event data" that take advantage of automated coding from news media have gained widespread recognition: International Crisis Early Warning System (ICEWS), maintained by Lockheed Martin, and Global Data on Events Language and Tone (GDELT), developed and maintained by Kalev Leetaru at Georgetown University (2, 3). The scale of these programs is unprecedented, and their promise has been reflected in the attention they have received from scholars, media, and governments. However, they suffer from major issues with respect to reliability and validity. Opportunities exist to use new methods and to develop an infrastructure that will yield robust and reliable "big data" to study global events - from conflict to ecological change (3).

"Man is by nature a political animal," as asserted by Aristotle. This political nature manifests itself in the data we produce and the traces we leave online. In this tutorial, we address a number of fundamental issues regarding mining of political data: What types of data would be considered political? What can we learn from such data? Can we use the data for prediction of political changes, etc? How can these prediction tasks be done efficiently? Can we use online socio-political data in order to get a better understanding of our political systems and of recent political changes? What are the pitfalls and inherent shortcomings of using online data for political analysis? In recent years, with the abundance of data, these questions, among others, have gained importance, especially in light of the global political turmoil and the upcoming 2016 US presidential election. We introduce relevant political science theory, describe the challenges within the framework of computational social science and present state of the art approaches bridging social network analysis, graph mining, and natural language processing.

2015

Do formal deliberative events influence larger patterns of political discussion and public opinion? Critics argue that only a tiny number of people can participate in any given gathering and that deliberation may not remedy - and may in fact exacerbate - inequalities. We assess these criticisms with an experimental design merging a formal deliberative session with data on participants’ social networks. We conducted a field experiment in which randomly selected constituents attended an online deliberative session with their U.S. Senator. We find that attending the deliberative session dramatically incresed interpersonal political discussion on topics relating to the event. Importantly, after an extensive series of moderation checks, we find that no participant/nodal charactersitics or dyadic/network characteristics, conditioned these effects; this provides reassurance that observed, positive spillovers are not limited to certain portions of the citizenry. The results of our study suggest that even relatively small-scale deliberative encounters can have a broader effect in the mass public, and that these events are equal-opportunity multipliers.

The increasing abundance of digital textual archives provides an opportunity for understanding human social systems. Yet the literature has not adequately considered the disparate social processes by which texts are produced. Drawing on communication theory, we identify three common processes by which documents might be detectably similar in their textual features - authors sharing subject matter, sharing goals, and sharing sources. We hypothesize that these processes produce distinct, detectable relationships between authors in different kinds of textual overlap. We develop a novel n-gram extraction technique to capture such signatures based on n-grams of different lengths. We test the hypothesis on a corpus where the author attributes are observable: the public statements of the members of the U.S. Congress. This article presents the first empirical finding that shows different social relationships are detectable through the structure of overlapping textual features. Our study has important implications for designing text modelling techniques to make sense of social phenomena from aggregate digital traces.

2014

Developing technologies that support collaboration requires understanding how knowledge and expertise are shared and distributed among communuity members. We explore two forms of knowledge distribution structures, coordination and cooperation, that are central to successful collaboration. We propose a novel method for detecting the coordination of strategic communication among members of political communities. Our method identifies a "rapid semantic convergence," a sudden burst in the use of linguistic constructions by multiple individuals within a short time, as a signature of coordination. We apply our method to the public statements of U.S. Senators in the 112th U.S. Congress and construct coordination and coopetation networks among these individuals. We then compare aspects of these networks to other known properties of the Senators. Results indicate that the detected networks reflect underlying tendencies in the social relationships among Senators and reveal interesting differences in how the different parties coordinate communications.

Politics is, at its core, a network phenomenon. Power - the central construct of political science - is intrinsically relational, where power exists between actors and among actors in a complex, differentiated fashion. India looms large for Nepal, not for Iceland. My boss is important to me, not you. More generally, we talk to people who affect what we think. Access and relationships among the powerful is indisputably important. One of the major subfields of political science is actually called international relations. And, as discussed below, there is a long standing interest in political science in networks, from the first years of the emergence of sociometrics. Perhaps the earliest effort in detecting clusters from relational data, one of the hottest areas in the study of networks currently, appeared in the American Political Science Review - in 1927 (Rice, 1927)! The first author on the first paper in the first issue of Social Networks was by one of the giants of the 20th Century political science, Ithiel de Sola Pool. This paper, circulating in unpublished form starting in the 1950s, was also the first to formulate the small world problem. One of the key drivers of the interest in networks the last 20 years has ben the vein of research on social capital - in part kicked off by research by a political scientist, Putnam et al. (1993), Putnam (2001). Given this history, it is therefore surprising that in the 20th century networks as a construct did not find a comfortable home within the discipline of political science, with a minimal presence in disciplinary journals. This has changed dramatically in the last decade, as part of a broader upsurge in interest in networks within the academy. One small illustration of this may be seen by the increase in the presence of networks at the annual meeting of American Political Science Association. A perusal of the program would have yielded few if any explicitly network related papers in any given year in the 1990s. In contrast, in the 2013 program, there are 23 network-themed panels, and over 100 papers explicitly evoking network concepts and data. This special issue thus represents an overdue reunion for the discipline and social network analysis. Our objective in this paper is to provide an overview of the trajectory of the research on political networks, and to place the contributions in this issue in that context. We begin with a short intellectual history of the long standing, if thin, history of network scholarship in the study of politics, maneuvering through the various, loosely coupled subfields of political science, and concluding with a discussion of what impact political science will have on the field of social networks as both move forward together.